Context

Between 2001 and 2008 investment in drug treatment increased from £250 million a year to £750 million a year. This yielded:

- Improved access to treatment with the numbers treated each year increasing from 80,000 to 230,000 and waiting times reducing from nine weeks to 5 days.

- Steady improvements in treatment quality reducing early dropout and increasing successful completion.

- Very low levels of HIV prevalence among injecting drug users and significant reductions in injecting drug use.

- Significant reductions in the incidence of heroin and crack use with the number of new young heroin users declining rapidly.

- Dramatic reductions in drug related crime. Ready access to treatment is responsible for a third of the overall reduction in crime this century according to Home Office research .

The 2010 drug strategy sought to build on this legacy. Despite the very challenging financial climate, investment was maintained at 2008 cash levels to lock in the public health and crime reduction benefits of the preceding decade to which the Home Secretary added a clear ambition to maximise the number of people recovering from addiction.

Local Authority Leadership

In 2013 local authorities assumed responsibility for commissioning drug and alcohol treatment and the resources previously channelled by the Department of Health through PCT’s for this purpose shifted to the public health grant, accounting for around a third of the total LA public health spend in 2013/14.

Treatment providers welcomed local authorities assuming leadership of this agenda as an opportunity to align clinical treatment services with the wider social supports required to enable individuals to recover; stable housing, routes into employment, family support etc. There was however significant concern that the achievements since 2001 and the recovery ambitions of the 2010 drug strategy would be undermined by disinvestment. Drug treatment was seen as being particularly vulnerable to disinvestment. Political pressure would inevitably push hard pressed local authorities to protect spend on more politically attractive vulnerable groups; the elderly, children etc. The societal benefits delivered by drug treatment accrue to the criminal justice system and the NHS not local authorities. Within public health drug addiction was not a natural priority. For every death attributable to drug addiction 10 arise from alcohol and a hundred from smoking. There was therefore concern that even if local authorities protected the overall public health spend directors of public health would cannibalise the very large current expenditure on drug treatment to reinvest elsewhere.

Disinvestment: risk or reality?

There are two dramatically different narratives about how events have played out since 2013. The official version based on local authority returns to DCLG point to investment holding up remarkably well. Despite inevitable local variation the national picture suggests cash investment holding steady and the fears of 2013 to have been exaggerated. The alternative narrative focuses not on returns to central government but on the value of actual contracts let to NHS and third sector providers to deliver services. Collective Voice regularly consults with local authority commissioners, clinicians, local NHS managers, and the leaders of smaller third sector providers. All of these consistently expressed scepticism about the accuracy of the national returns and report a consistent picture of widespread and significant reduction in contract value. This is reflected in a recent exercise undertaken by Collective Voice drawing down information readily available about drug and alcohol treatment investment from local authority websites.

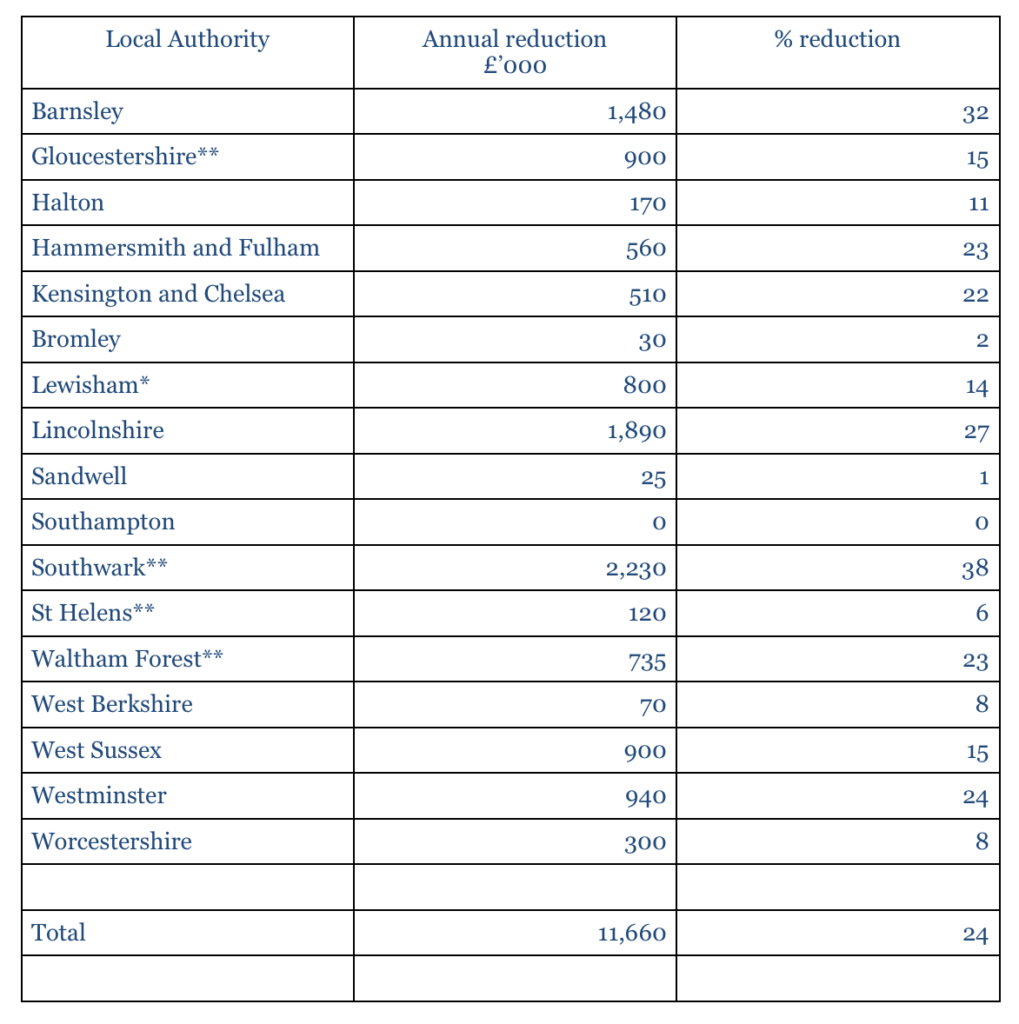

Reductions in contract values from 2014/15:

*Lewisham also reduced their contract value by £300k (5%) in 2013/14.

*Lewisham also reduced their contract value by £300k (5%) in 2013/14.

**These figures are annualised as the data available was for the total contract period, not per annum.

Across the 17 local authorities listed, three effectively have a standstill budget, three budget for a reduction of under 10%, four show a reduction between 10% and 20%, five between 20 and 30%, and two over 30%. The average reduction per local authority is 15% and the overall reduction in spend across the 17 local authorities is 24%.

At the very least the discrepancy between the reassuring message about resources emanating from the LGA and DCLG and the cash reductions reported by local authorities requires further investigation.

Implications

Cost reductions do not inevitably mean reductions in quality or outcomes. Investment grew very rapidly over less than a decade and was not always deployed with optimum efficiency.

Since 2008 providers have worked very closely with commissioners to redesign individual services and local systems to obtain better value from flat and reducing budgets. There are numerous examples across the country of services being able to absorb significant reductions in budgets while delivering higher volumes and better outcomes. However the very fact that this period of retrenchment has been the norm for longer than the period of growth suggests that the easy efficiency gains have been won. The 20% cut to the Public Health Grant announced in the spending review will tighten resources further putting even more pressure on services to innovate if outcomes are to be protected. Other changes in the operating environment make this even more challenging.

The decline in new young heroin users means that those now in treatment are disproportionately middle-aged with poor physical and mental health. They are ageing rapidly becoming frailer and more likely to succumb to drug-related deaths. Their needs require an integrated local authority NHS response which the current framework of collaboration through Health and Wellbeing Boards is failing to recognise and which will demand ever greater resources. At the same time the wider network of recovery services; housing, employment, mental health, family support, required to turn the government’s recovery ambition into reality, are themselves under increasing strain reducing their capacity to work in partnership with treatment services. This is already showing itself in negative impacts on outcomes.

The tightening of the financial environment over the past eight years, the prospect of further significant cuts, increasing fragility of the treatment population, and the compounding impact of reductions in related services have all combined to alert other government departments to the potential impact for their agendas of future disinvestment from drug and alcohol treatment. The Home Office and Ministry of Justice are acutely concerned about maintaining access to treatment as they continue to value the crime reduction benefits it yields. DWP’s efforts to route drug and alcohol misusers into employment are heavily dependent on an accessible effective treatment system. No 10’s Life Chances Strategy sees recovery from dependence as a route out of poverty for adults and their children.

Providers of drug and alcohol treatment and recovery services in the third sector and the NHS will continue to work with commissioners to extract best value from public investment but it will become increasingly difficult to sustain cuts at the levels described above without jeopardising outcomes and impact. Collective Voice would hope that the forthcoming refresh of the Drug Strategy recognises and addresses this challenge.

Paul Hayes

CEO Collective Voice

April 2016.

Related Content

We are deeply sad to share news of the death of the Chair of Collective Voice Lea Milligan

With great sadness, we share news of the death of Collective Voice’s Chair of Trustees Lea Milligan who passed away on Monday 15 April following

Watch: Women Supporting Women, International Women’s Day 2024

On International Women’s Day 2024 the Collective Voice Women’s Treatment Working Group hosted a webinar to explore and share good practice when working with women in drug and alcohol treatment services.

The impact of the cost of living crisis on drug and alcohol treatment and recovery

The impact of the cost of living crisis further emphasises the need for long term and sustainable funding for drug and alcohol treatment and recovery services.